I sleep more poorly than I hoped, given how tired I am. It is warm in my room, and using the fluffy duvet—the only bed covering available—leaves me too hot, and going without it leaves me too cold. This is one of those times when having a top sheet and blankets works better than this British way of having only a bottom sheet and a duvet on a bed.

I sleep more poorly than I hoped, given how tired I am. It is warm in my room, and using the fluffy duvet—the only bed covering available—leaves me too hot, and going without it leaves me too cold. This is one of those times when having a top sheet and blankets works better than this British way of having only a bottom sheet and a duvet on a bed.This morning I do TTouch on my legs and feet to ease tight muscles and sore ankles. I recall Tracy’s warning at St Bees—it’s not each day’s trek that’s the challenge, it’s the daily repeat of it that’s the thing.

I am off at 9:20a after the typical full English breakfast and a last-minute repair to my trekking poles. The foam handles have lost their glue and slide down whenever I push on them for support. Some Elastoplast wrapped below the grip solves the problem. I’ve also remembered to request a sack lunch today, and I load myself up with water and Tracey’s ample meal of sandwich, crisps, biscuit, fruit, KitKat, and juice. As I leave, I sample a ripe raspberry from a vine stretching over her garden wall.

The bridge that leads to the C2C path is just outside Tracey’s B&B. I am onward to Grasmere by one of two routes: a high walk along the ridge, or a shorter, more direct route through the valley. The decision point comes later, after Lining Craig. Not sure yet which trail I’ll choose.

The bridge that leads to the C2C path is just outside Tracey’s B&B. I am onward to Grasmere by one of two routes: a high walk along the ridge, or a shorter, more direct route through the valley. The decision point comes later, after Lining Craig. Not sure yet which trail I’ll choose. This part of the walk—a two-day jaunt to Patterdale—is one of Wainwright’s favorites. Rather than go directly over a wall of fells that run north-south, the track requires a jog south through Grasmere and then back north to Patterdale along footpaths that follow ridge lines or go through valleys. The eight-miles-as-the-crow-flies trip to Patterdale is doubled by this detour.

This part of the walk—a two-day jaunt to Patterdale—is one of Wainwright’s favorites. Rather than go directly over a wall of fells that run north-south, the track requires a jog south through Grasmere and then back north to Patterdale along footpaths that follow ridge lines or go through valleys. The eight-miles-as-the-crow-flies trip to Patterdale is doubled by this detour.

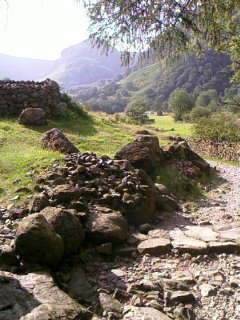

I meet Barry from Manchester along the lovely Greenup Gill (a river, now very low because of the hot summer) that flows through Borrowdale outside of Stonethwaite. He’s on a few days’ walk, not the C2C, and is going to Grasmere for his last day. I quiz him about the two trail choices ahead, and he recommends the high road. We’re staying at the same hostel in Grasmere—there are two there, the place is such a popular stopover.

I meet Barry from Manchester along the lovely Greenup Gill (a river, now very low because of the hot summer) that flows through Borrowdale outside of Stonethwaite. He’s on a few days’ walk, not the C2C, and is going to Grasmere for his last day. I quiz him about the two trail choices ahead, and he recommends the high road. We’re staying at the same hostel in Grasmere—there are two there, the place is such a popular stopover.He becomes a dot ahead of me on the way past Eagle Crag, and two fellows in their early twenties later puff by me carrying packs large enough to hold camping gear. They, too, become dots near the top of Lining Crag, even when I’m at the bottom of it.

The day is turning warm, and the prospect of Lining Crag, that hill to the left in his photo, daunts me. It is steeper and longer than yesterday’s Loft Beck, and looks like it’s full of scree and those ankle-breakers I dealt with yesterday. I start up the hill, one foot in front of the other, trekking poles at the ready, winding left then right then straight up, and frequently finding blessed sets of stone steps that hardy C2C volunteers have installed to help keep down erosion.

The day is turning warm, and the prospect of Lining Crag, that hill to the left in his photo, daunts me. It is steeper and longer than yesterday’s Loft Beck, and looks like it’s full of scree and those ankle-breakers I dealt with yesterday. I start up the hill, one foot in front of the other, trekking poles at the ready, winding left then right then straight up, and frequently finding blessed sets of stone steps that hardy C2C volunteers have installed to help keep down erosion.I am again pausing every hundred feet or so on the ascent, winded and panting, which I find utterly appalling, and I use each stop as an excuse to look back upon the dale, the gill, and how far I’ve come from Stonethwaite. A 30’s-something couple passes me about two-thirds of the way up. We don’t expend the energy to say more than hello. I stick a pole to the next rock and keep going.

I finally reach the summit of Lining Crag and take the detour to its very top for a rest rest rest and to take in the well-earned spectacular view. I am breathing hard, pink in the face, and ready to fall down on the spot. There I meet the two young guys who had passed me, packs on the ground, sweat on their shirts, sitting on two boulders.

I finally reach the summit of Lining Crag and take the detour to its very top for a rest rest rest and to take in the well-earned spectacular view. I am breathing hard, pink in the face, and ready to fall down on the spot. There I meet the two young guys who had passed me, packs on the ground, sweat on their shirts, sitting on two boulders.One is on his cell phone. The other is smoking a fag.

I laugh outloud at the absurdity of it all. They are David and Wessel from Holland, out to walk the C2C in 10 days (the average is 14) before going south to meet David’s family, who still live in England. They need to make it to Patterdale tonight—over 16 miles from Rosthwaite, traveling the most grueling part of the trail and carrying full packs. They’re already thinking about hiring the Sherpa Van for the rest of the trip.

The route from Lining Crag to Grasmere requires going over a pass called Greenup Edge toward a place called the head of Far Easedale, and then following a stream straight down to Grasmere. The fact that Wainwright warns that it’s easy to fall into the “Wythburn trap” (to mistake the Wythburn valley stream as the Far Easedale path and thereby end up on the wrong side of the ridge from Grasemere) does not ease my mind. I ask to join David and Wessel over this next tricky bit of Greenup Edge.

This time I’m the one with the OS map, and David, who did this walk two years ago, has a vague idea which way to go. The top of the Greenup Edge is squishy peat and tall grasses. No signage is to be found, and the only waymarkers that Wainwright lists are landmarks such as “old fence,” “the remains of a wire fence,” and “an iron stile incongruously standing in isolation.” About as much help as the names of the locales themselves. (Why do people even bother to refer to geographical names at all on walks like this; I mean, it’s not like I’m going to find a sign up here that reads, “Welcome! You are at Greenup Edge. The Head of Far Easedale is that way. Turn left for Grasmere.”)

Fortunately, the weather is also with us, and the glorious, mist-free day allows us to see Grasmere in the distance as we, miracle of miracles, actually do spot a bit of rusting iron stile sticking incongruously from a nondescript pile of granite and grasses.

With the lake of Grasmere in sight almost five miles away, I practically skip down the rock-strewn gully of a now-dry stream, stepping on the big stones and letting gravity take me to the next one. It becomes almost a dance—balancing and falling forward to catch the next rock instead of trying to pick my way around and between them. I skim down the hill the entire way, gleeful as a child tripping across a river on stepping stones.

The boys and I soon reach our split-off point: the junction of the ridge walk to the left and the valley walk straight into Grasmere, with the sweep of Grasmere Common banking the right side. They take the shorter, direct route in hopes of getting there for lunch. I decide to try my hand and feet at the high-rise walk along Calf Crag, Gibson Knott, and Helm Crag. I can follow the ridgeline visually from here, three summits that will afford some great views of where I’ve been and where I’m headed. Wainwright says it adds a mile to the walk and an hour to the time, and is worth the additional effort.

The boys and I soon reach our split-off point: the junction of the ridge walk to the left and the valley walk straight into Grasmere, with the sweep of Grasmere Common banking the right side. They take the shorter, direct route in hopes of getting there for lunch. I decide to try my hand and feet at the high-rise walk along Calf Crag, Gibson Knott, and Helm Crag. I can follow the ridgeline visually from here, three summits that will afford some great views of where I’ve been and where I’m headed. Wainwright says it adds a mile to the walk and an hour to the time, and is worth the additional effort.I take inventory. So far my feet and legs are holding up well. Water supply is good. I’m hungry, so I eat my sandwich and get going again before 12:30. Just as I am climbing along an old fence line to the ridge, four ravens come soaring from beyond Calf Crag and fly around over me before heading off.

Calf Crag, at 1,800 feet, offers amazing views, which I video in a panorama using Perry. The walking is easy along this ridgeline, and very windy. A cairn is at the top of the crag, and I add a stone to it.

Calf Crag, at 1,800 feet, offers amazing views, which I video in a panorama using Perry. The walking is easy along this ridgeline, and very windy. A cairn is at the top of the crag, and I add a stone to it.

I sit here at the top of Calf Crag, looking ahead to Grasmere and to the third ridge for today, Helm Crag, and feel so proud of myself for doing this walk. I wanted to back out at the beginning, and I’ve had help and support all along the way, plus time to find my own way for miles.

I sit here at the top of Calf Crag, looking ahead to Grasmere and to the third ridge for today, Helm Crag, and feel so proud of myself for doing this walk. I wanted to back out at the beginning, and I’ve had help and support all along the way, plus time to find my own way for miles. Watching the trail ahead instead of the ground today has been pushing me to use my peripheral vision to guide my feet in all but the most sticky places. I’m trusting my body more too. I feel stronger, knowing when to rest, when to pause to deal with sore feet, when to eat, drink, or soak in the view. The tune of “My Boyfriend’s Back” runs through my head with different lyrics: “My vision’s back and it’s gonna stay forever. Hey now, hey now, my vision’s back.” It’s true, too—my distance vision is definitely sharper, the more I relax into my own self guidance in the day.

Watching the trail ahead instead of the ground today has been pushing me to use my peripheral vision to guide my feet in all but the most sticky places. I’m trusting my body more too. I feel stronger, knowing when to rest, when to pause to deal with sore feet, when to eat, drink, or soak in the view. The tune of “My Boyfriend’s Back” runs through my head with different lyrics: “My vision’s back and it’s gonna stay forever. Hey now, hey now, my vision’s back.” It’s true, too—my distance vision is definitely sharper, the more I relax into my own self guidance in the day. At Gibson Knott, I stop for a snack with Grasmere lake in closer view and take time to belt out songs to the hills. The same kind of joy is bubbling through me as when I was walking on Jura. I love this place, this day, this moment. Myself.

At Gibson Knott, I stop for a snack with Grasmere lake in closer view and take time to belt out songs to the hills. The same kind of joy is bubbling through me as when I was walking on Jura. I love this place, this day, this moment. Myself.Two swallows speed by doing aerobatics like F-16s; they actually make a whizzing sound, they are moving so fast. A kestrel or similar bird hovers over the heath. Its outspread wings catch the wind, and it hangs motionless in the air. I find a large fluffy, air-worthy feather anchored to the ground by pellets of sheep shit. The analogy isn’t lost on me—lighten my load of unnecessary stuff, and I’ll be able to float on the breeze.

Two hours after first getting to the ridge, I reach the third hilltop, Helm Crag, also known as the Lion and Lamb. Thank god for volunteers who keep up this trail. There are stone steps on the steepest of most ascents, and their welcome regularity of stride makes for happier knees here at Helm Crag. By now, my body is beginning to feel the strain of the day’s continuous up and down. Looking back to the west, I photograph where I’ve come from. “I did that. I walked the ridge.” Some do Mt Everest. I did this fell range.

Two hours after first getting to the ridge, I reach the third hilltop, Helm Crag, also known as the Lion and Lamb. Thank god for volunteers who keep up this trail. There are stone steps on the steepest of most ascents, and their welcome regularity of stride makes for happier knees here at Helm Crag. By now, my body is beginning to feel the strain of the day’s continuous up and down. Looking back to the west, I photograph where I’ve come from. “I did that. I walked the ridge.” Some do Mt Everest. I did this fell range. Grasmere and its lake are beautiful seen from Helm Crag. It’s an awful walk down to get there, though: punishing in its scree and rocks and steep pitch. “Please, level road!” my ankles and knees keep begging of every turn. It takes me forty-five minutes to make the descent, and every step shoots pain through my leg joints.

Grasmere and its lake are beautiful seen from Helm Crag. It’s an awful walk down to get there, though: punishing in its scree and rocks and steep pitch. “Please, level road!” my ankles and knees keep begging of every turn. It takes me forty-five minutes to make the descent, and every step shoots pain through my leg joints.The last mile into the hostel is blissfully tarmac, albeit a bit uphill, and I reach the YHA at 4:00p, just in time to check in, get settled into a bunk, and go back out to wander around Grasmere in hopes of picking up a few things before stores close at 5:00. Weather reports look good for tomorrow—more sun, no rain.

I’ve been to Grasmere before, over 25 years ago as part of a two-week UK bus tour I took with my grandparents after I graduated from high school. I forgot how large the town is—and it seems to have grown. Lots of stores, hotels, restaurants, bookshops, side streets. A veritable metropolis after so many nearly one-street villages of the last few days.

Grasmere’s most famous son is William Wordsworth, who lived here most of his life and is buried just across from where I sit right now. I’m in a lovely garden that volunteers started two years ago from a waste area. It’s tranquil and shady and right next to the church Wordsworth attended and the cemetery where he helped plant a lot of yew trees that are now almost 150 years old. The town has planted 3,000+ daffodils in this park and they are slowly paving the walkways with stones bought by sponsors. Benches, too. They want to plant an oak tree in one of the corners—no one has stepped up to buy it yet.

Grasmere’s most famous son is William Wordsworth, who lived here most of his life and is buried just across from where I sit right now. I’m in a lovely garden that volunteers started two years ago from a waste area. It’s tranquil and shady and right next to the church Wordsworth attended and the cemetery where he helped plant a lot of yew trees that are now almost 150 years old. The town has planted 3,000+ daffodils in this park and they are slowly paving the walkways with stones bought by sponsors. Benches, too. They want to plant an oak tree in one of the corners—no one has stepped up to buy it yet.There’s a Wordsworth Hotel and Restaurant in Grasmere. Lots of Wordsworth china, books, tourist trinkets, etc. I wonder what good old William would think of all this merchandizing in his name. He’d probably like the garden.

Lots of people are walking by as couples. How nice that would be to have at the moment. I feel sad that I didn’t connect with Michael and David today. I wonder if they took the short route in.

I find a walking shop and buy a second pair of shorts for my wardrobe. The weather’s been warm all day, with good breezes and some cloud-shadowed sun. The top of my thighs got sunburned. I can feel their heat through my black slacks.

I eat a popsicle, Hula Hoops, and a Snickers bar to replenish my energy enough to walk the mile back to the hostel. Physically, I am exceptionally tired—weary feet and legs. At my core though, I feel very fit and calm and pleased with myself. Walking, exercise, is good.

Waiting for dinner at the hostel, I meet up with the couple from Australia whom I’d met last night at the pub in Rosthwaite. Elaine and John. They are outgoing and easy, and I like them both.

John has made a huge project of the walk preparation—laminated, color-coded printouts of each day’s trek, with abbreviated notes about landmarks and interesting spots to see along the way, and enlarged maps of the route. Even punched holes in the sheets so he can wear them around his neck and refer to them as they walk. It took him months to research everything on the web and set it all up.

I’m both impressed and amused. That kind of detailed, organized groundwork is something I would have done years ago—and might have done still, had I not chosen to go more serendipitously on this trip. I begin to judge all that setup as anal, then realize that that kind of deep preparation is undoubtedly vital for safety and survival when walking in Australia’s wilds, as John and Elaine often do. Certainly it alleviates the fear factor of getting lost.

Barry joins me for dinner at the hostel, and John and Elaine, who often do their own cooking in hostel kitchens, join us for company. The hostel staff has taped balloons and a Happy Birthday message to the end of the table I’m sitting at. A little girl is celebrating her birthday with her family. Her little sister is going around with Daddy’s big digital camera taking pictures of everything in macro mode, from her own waving hand to the frosting on the cake to strangers like me eating rice and curry.

Barry joins me for dinner at the hostel, and John and Elaine, who often do their own cooking in hostel kitchens, join us for company. The hostel staff has taped balloons and a Happy Birthday message to the end of the table I’m sitting at. A little girl is celebrating her birthday with her family. Her little sister is going around with Daddy’s big digital camera taking pictures of everything in macro mode, from her own waving hand to the frosting on the cake to strangers like me eating rice and curry.Three days ago, in the heat wave from St Bees to Ennerdale Bridge, I was beginning to question the wisdom of this trek, and reading Wainwright’s book in between hasn’t always instilled confidence in my decision to do it. Had I gone through Wainwright’s book before leaving the U.S., or done the kind of research that John did on the C2C, I probably would have bagged the whole idea. I’m glad I didn’t.

I’ve read that the first days on the eastbound walk are grueling ways to get in shape for the rest of the C2C. Looking back, the path hasn’t been hard per se, but it has been strenuous and rough going, requiring significant stamina—and sometimes plain old stubbornness—just to keep on track.

Until today, I’ve also felt an underlying urgency to get to each day’s destination on the map, to not dawdle too long, to make sure I don’t run out of time. Now I’m beginning to settle into the feel of the walking itself, and am finding a rhythm in which my body knows how many hours it takes to go a certain distance. This allows me to pace myself better and to take more time out to enjoy where I’m at.

Fell walking is not for the faint of heart, although it is growing on me. The hills aren’t as intimidating now that I’ve met them. As strangers, they were unreadable and frightening. But having walked them, viewed them, followed their contours, found them labeled on maps, I’ve made friends with them safely.

Fell walking is not for the faint of heart, although it is growing on me. The hills aren’t as intimidating now that I’ve met them. As strangers, they were unreadable and frightening. But having walked them, viewed them, followed their contours, found them labeled on maps, I’ve made friends with them safely.And their heights are manageable. There are no permanently snow-covered peaks that require special gear to climb, or that give me altitude sickness. The trails here lead me to places, instead of just being fresh-air loops or arduous climbs that I walk for the sake of walking. “Think I’ll go to Grasmere.” Snap. I can do it in a day.

Having seen them first-hand, I can see why Wainwright calls these fells and dales “delectable,” and proclaims today’s walk to be “a walk in heaven.” While I never expected heaven’s steps to be so hard on the knees, I agree.

Trail miles: 8; actual miles walked: 10